Cobras are opportunistic predators with large appetites. They primarily feed on reptiles, amphibians, small mammals and, more rarely, birds3. In Morocco, cobras appear to consume large quantities of snakes.

North African Cobra

Naja haje

A powerful symbol of Moroccan biodiversity, the North African cobra is one of the most iconic and impressive snakes of the Maghreb. As a top predator, it plays a vital role in maintaining ecological balance by controlling rodent populations. Yet this once widespread species is now in sharp decline. It faces serious threats from habitat degradation, targeted captures by snake charmers, and widespread fear that often leads to persecution. Now a striking emblem of the growing tensions between human communities and wildlife, Naja haje highlights the urgent need for thoughtful and effective conservation efforts.

The North African cobra (Naja haje) is a venomous snake and the only representative of the Elapidae family in Morocco. It can also be found in Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, as well as in the Sahel region, from Niger to Somalia. It is also possible that a small intermediate population still persists in Algeria. The Moroccan population, relatively isolated, displays distinct visual characteristics compared to other populations of the species. These morphological differences led to the Moroccan cobra being long considered as a subspecies (N. h. legionis), or even as a separate species (Naja legionis). However, in 2009, a study conducted by Trape et al. demonstrated that the cobras of Morocco are not genetically distinct from other North African populations and have therefore classified it within Naja haje. Furthermore, certain other subspecies of Naja haje have been reclassified as distinct species1. To date, no subspecies of Naja haje is officially recognized.

In Morocco, the cobra's size generally does not exceed 1.50 meters, although some large males can reach nearly 2 meters. As adults, they display a uniformly black color with bronze reflections that appear on the flanks and, in some cases, extend to the back. Their eyes are entirely black, and they have a small white spot under the head, a distinctive trait of Moroccan specimens. Juveniles, on the other hand, have a sand-colored appearance adorned with black lines or spots. Their head and hood are already black from birth. The North African cobra's snout is rounded, and its head is covered with large scales.

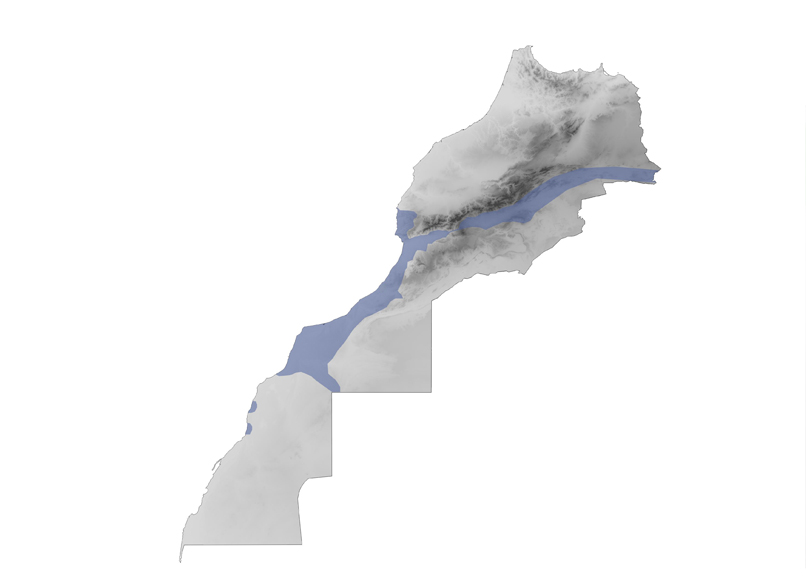

The North African cobra (Naja haje) is primarily known to be present in the region of Sidi Ifni, Guelmim and Tan-Tan, where its density is believed to be highest. Its range would extend southward to Laâyoune and northward to Agadir, climbing up the Souss valley. It is also found on the western foothills of the southern Atlas, from Ouarzazate to the Tinghir region51.

Although it lives in semi-arid areas, this snake seems to prefer slightly more humid habitats. It often takes refuge near riverbanks, under bushes or in underground galleries dug by squirrels and rodents.

This snake has excellent vision and reacts very quickly to movements. It is also lively and fast, allowing it to effectively flee from danger. When taking flight, it often emits a deep hiss by expelling air, which causes a small cartilage structure in its throat to vibrate2.

Its famous hood, entirely black and relatively elongated, is not solely a means of defense. It sometimes extends it when basking in the sun to absorb heat more quickly. It can also deploy it while fleeing, without necessarily raising its head.

The North African cobra adopts the classic cobra posture, with the head raised and the hood deployed, only when cornered and can no longer flee. In this situation, it seeks to impress the aggressor by appearing more imposing, while emitting powerful hisses. If the threat persists, it performs intimidation charges by projecting its body forward over a distance that can reach 70 cm for the largest individuals. Most of the time, these attacks are carried out with the mouth closed. If the danger continues to approach, the cobra may then attempt to bite.

Although this species is highly venomous, it does not systematically inject venom during a bite. The cobra controls and modulates the injection depending on the situation. Thus, it truly bites with venom injection only in the most extreme cases, when all its other deterrent attempts have failed.

The deployment of the hood with the head raised is precisely the behavior exploited by snake charmers. To achieve this, the snake is first removed from its box, then prevented from fleeing in order to force it to adopt this defensive posture. Once in this position, it is kept in a constant state of stress so that it doesn't relax its vigilance. This stress is maintained by the back-and-forth movements of the charmer and his flute, which the cobra perceives as a threat. In its eyes, these gestures mimic the movements of a predator hesitating to attack, which prompts it to remain alert and maintain its impressive posture.

Little is known about the reproduction of Moroccan Cobra in the wild. It is assumed to reproduce in spring and lay between 10 and 20 eggs, like other Naja haje populations4.

The species Naja haje is classified as "Least Concern" on the IUCN Red List. However, this classification applies to the species as a whole and does not necessarily reflect the situation in Morocco6.

This cobra appears to have been much more widespread in the Maghreb in the past than it is today. Its decline is probably due to several factors:

- Habitat destruction due to urbanization

- Systematic killing by the local population

- Indirect poisoning after ingestion of rodents contaminated by pesticides

- Massive collection of individuals to be sold to snake charmers6

In some regions, intensive collection by itinerant snake hunters has led to a near-local disappearance of the species.

- Trape, J.-F., Chirio, L., Broadley, D. & Wüster, W. (2009). Phylogeography and systematic revision of the Egyptian cobra (Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja haje) species complex, with the description of a new species from West Africa. Zootaxa, 2236: 1–25.

- Russell, A.P. & Bauer, A.M. (2021). Vocalization by extant nonavian reptiles: A synthetic overview of phonation and the vocal apparatus. The Anatomical Record, 304(7): 1478–1528.

- Shine, R., Branch, W.R., Webb, J.K., Harlow, P.S., Shine, T. & Keogh, J.S. (2007). Ecology of cobras from southern Africa. Journal of Zoology, 272(2): 183–193.

- Behler, J. & Brazaitis, P. (2007). Breeding the Egyptian cobra: Naja haje: at the New York Zoological Park. International Zoo Yearbook, 14: 83–84.

- iNaturalist. (2025). Naja haje observations in Morocco. Available from https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?taxon_id=30479. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- IUCN SSC Snake Specialist Group. (2021). Naja haje. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021.